French President Nicolas Sarkozy has ordered his government to draft a new law punishing denial of the Armenian genocide. The French parliament recognized the killing of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War as genocide in 2001. In December 2011, The French MPs went further, approving a bill that would make denying the Armenian genocide a criminal offence punishable by a one-year prison sentence and a fine of 45,000 euros. France’s top court struck it down last month as unconstitutional. Sarkozy, running for re-election next month, stressed again to the Armenian Diaspora in France (around half a million strong) his commitment to a new law.

by Hatim Suleiman

Away from election politics and the contradicting French official denial of France’s own dark history in Algeria, I cannot help thinking of the intertwining cultures of Anatolia (or Asia minor) and its painful twists of history, I cannot help thinking of Tatyos Efendi.

Beyond the beautiful Armenian Duduk music of Djivan Gasparyan, the rich liturgical music of the oldest Christian nation in the world, and the many opera and classical composers of “Soviet Armenia”, stands Kemani (violist) Tatyos Ekserciyan (or simply Tatyos Efendi meaning ‘Mr. Tatyos‘), one of the best composers of Ottoman classical music. Tatyos Ekserciyan was born in 1858 in Ortaköy district of Istanbul as the son of a musician at the Ortaköy Armenian Church. Growing up, he worked in some traditional crafts before turning to music and learning the Qanun. He then moved on to learn singing, musical theory and violin which eventually gave him the title Kemani (violist). His teachers include great musicians of his time as Asdik Aga and the violin teacher Kemani Sebuh (also an Armenian).

Accompanied by the great musicians of the latest ottoman era at the end of the 19th century (such as Ahmed Rasim Bey, Civan and Andon Brothers, Şevki Bey, Kemenceci Vasilaki and Tanburi Cemil Bey) Tatyos was a court musician of Sultan Abdel Hamid II and played in famous clubsof Istanbul such as the Pirinççi Night Club. His alcohol drinking problems got hold of him eventually and he died as a lonely miserable man at the age of fifty-five in 1913, just before the start of the First World War and the final collapse of Ottoman Empire. He was buried in the Armenian cemetery in Kadikoy district of Istanbul.

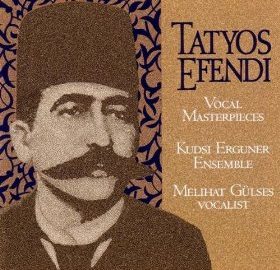

Tatyos Efendi pieces continue to be played not only in Turkey, but also in Greece, Cyprus, the whole Arab world and wherever classical middle eastern music is played (especially his instrumental works, since the vocal works are in Turkish with poems mostly written by himself). One of his songs is sung here by the famous Turkish singer Melihat Gülses:

The instrumental works, called (saz) Semai’s and pesrevs, are standard classical pieces taught in conservatories of middle eastern music around the world. Tatyos left us some of the most popular instrumental works of Ottoman classical music; only the works of his contemporary Tanburi Cemil (or Jemil) Bey come close. Because of the painful history, the Ottoman classical repertoire – seen as the as court music and the art of high Turkish elite – was not easily played and remembered by many Armenians in the Diaspora. Strangely enough, it was also frowned upon – almost banned – for years in the modern state of Turkey under Atatürk, for being too Ottoman.

The USA however has a rich history of Armenian recording artists playing in Middle Eastern style and singing in Turkish, such as the ud virtuoso Marko Melkon Alemsherian.

From the early 1990s, there has been a strong comeback of releasing records of Ottoman classical music both in Turkey and abroad. Armenian-American ud player Richard Hagopian paid tribute to Tatyos as part of Armenian ottoman heritage and recorded few of the Tatyos pieces, such as this one. The same popular instrumental piece is played here by an Egyptian ensemble in the early 1950s.

One of Tatyos most beautiful and popular pieces is the “Hüseyni Saz Semai”, played here by his contemporary: Tanburi Tanburi Cemil Bey. This is the same piece as recorded eight decades later, in the 1990s, by the ensemble of Paris based Turkish musician Kudsi Erguner, who recorded the complete works of Tatyos Efendi.

The Armenians in the Diaspora, like many other peoples forced to displace, still struggle with their history rooted in their former lands. The Armenian families’ history (spoken and written in Turkish), the heritage of the urban culture of the big cities like Istanbul, the great musicians who thought, sang and made music in the middle-eastern Ottoman style. This is a heritage totally – and naturally – claimed by Turkey. The majority of Armenians in the world come from the cities and villages currently in Turkey. While the Armenian diaspora looked at the newly independent Republic of Armenia as a place all Armenians could call home, the Republic of Armenia, emerging from decades of Soviet rule looked out to the Diaspora for a taste of authentic Armenian heritage. A heritage that was, despite all, well kept.

Reblogged this on Notes of a Spurkahye and commented:

Important Armenians in Ottoman History