It is fascinating to see musical changes in society. Sometimes these changes are linked to sociopolitical or economical motivations. Sometimes a culture tries to superimpose other cultures. Or sometimes music from other cultures is just a source of inspiration. It is never a one-way track, but rather back and forth, upside down, and inside out. In this article John Collins is going to enlighten us about the roots and the routes of African rhythms. This is a transcription (edited by Collins) of the lecture held at the World Blend on June 28, 2013, during the Jazz Days in Rotterdam. This World Blend carried the smart title: Bye Jazz, Hello World.

Mind you, this is a long read with lots of pictures and music.

by Charlie Crooijmans

Moderator Stan Rijven introduced John Collins as a Britisher who has lived in Ghana since the 1950s (now a naturalized Ghanaian) who is an author, an archivist, a musician and has been a consultant for artists like Brian Eno, Mick Fleetwood, Ian Dury and Jamie Cato (One Giant Leap). Collins played with Ghanaian and Nigerian bands/artists like the Jaguar Jokers, Kwaa Mensah, F. Kenya, Victor Uwaifo, Koo Nimo, the Bunzus, Atongo Zimba and T.O Jazz.

In the 1970s he ran his Bokoor Band in Accra and in the 1980s to mid90s operated his Bokoor Studio that recorded 200 bands and released 70 albums. In 1990 he established the Bokoor Music Archives in Accra and is currently a Music Professor at the University of Ghana and co-runs the Local Dimension highlife band with Aaron Bebe Sukura.

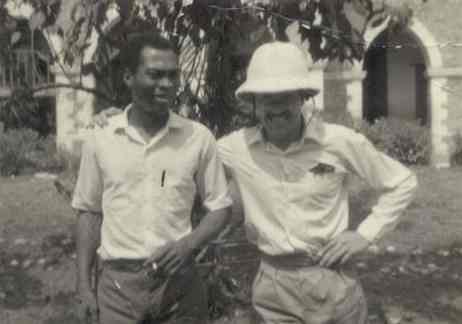

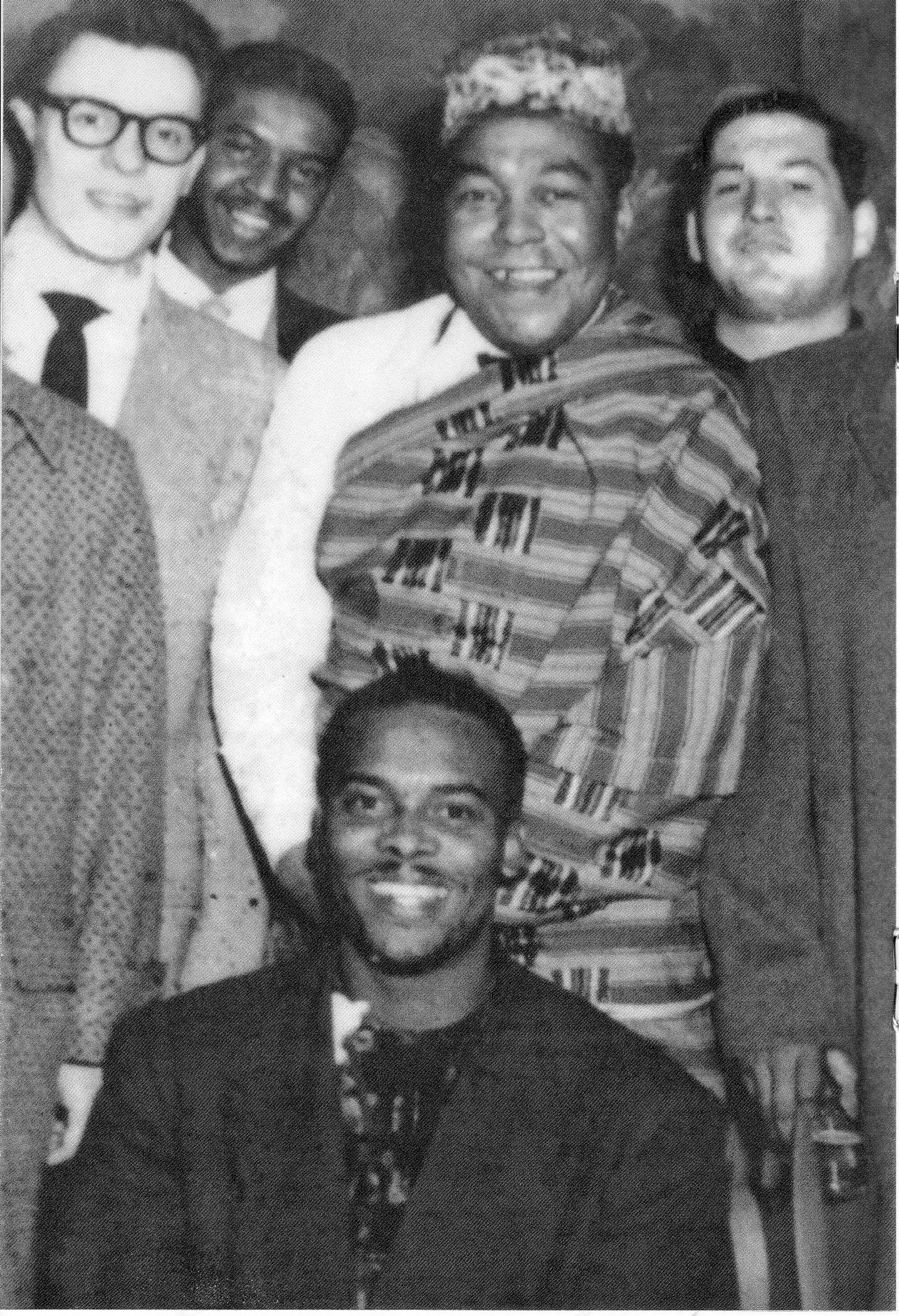

In the 1970s Collins worked with Fela Anikulapo Kuti on several occasions and on one of the slides he is to be seen with the late Fela in 1977 when he was asked to participate in Fela’s biographical movie The Black President in the role of colonial education officer.

In fact, Collins has just been invited to speak at the at the next Felabration in Lagos in October 2013 for its symposium on the role of Fela and Bob Marley for Black Mobilisation – Collins will talk on Fela, Nkrumah and the Ghanaian Connection.

In Collins’ Jazz Day presentation he first examined the parallels in the development of Jazz and Ghanaian brass band music – and then moved to the direct impact of Jazz on dance band Highlife.

Military weapon music

Highlife music started with brass band music. Basically the West Africans hijacked European brass band music and turned it in recreational music called Adaha, which is an early form of Highlife. Likewise Black Americans did exactly the same thing, they hijacked Western military music to create Jazz. In Ghana the British and the Dutch taught Africans to play brass band music, but in the beginning they didn’t want Africans to play their own music. They were being brainwashed. Don’t forget that brass band music is a military weapon music with bugles and drums being used for communication in warfare. Up to about the 1880s that was the situation. Africans could play brass band music, but only in European time.

Then during the Ashanti Wars of 1873 –1901 between 5,000-7,000 West Indians were stationed in Elmina and Cape Coast. The reason was that Ghana was then the ‘white man’s grave’. When the British sent their soldiers to Kumasi, to defeat the Ashanti people many of them died of or got sick with malaria. But the British noticed that the black Caribbean troops didn’t die. They didn’t know the reason. Now we know it’s the ‘sickle-cell’ effect. So you could say that the colonialists brought in tropicalized troops to help them to defeat the Ashantis. That’s the negative side of the story – the musical consequence is more positive.

Early form of Calypso

The West Indian presence was a boon for the Ghanaians, because of the rhythms and the music they brought. They introduced early forms of Calypso, and they brought the 5 pulse (3-2) claves or bell rhythm played in 4/4 time. Now this created a sensation for Ghanaians, as this 5 pulse rhythm is not an African rhythm, but is a mutated African rhythm. The original African rhythm is a 6/8 polyrhythm. And you have the five pulse (grouped as 1,2,3- 1,2) layered onto the various multiple rhythms of this polyrhythmic structure.

The whites slave masters in the Americas were petrified by this rhythm and also the traditional African drums that played them. The drums can talk and so was used to communicate and coordinate slave revolts (as in Haiti). Moreover, polyrhythmic drum music is religious and associated with ritual dancing which can power the Black slaves up religiously against the whites. So the Europeans and the whites Americans not only banned the talking drums, but also sacred African polyrhythmic music.

So what a lot of Africans did in different parts of the Americas ( Cuba, Trinidad, Brazil, Jamaica) is they took the 5- pulse bell/claves and boxed it into or 4/4 (or 2/4) time. This was safe as with these you cannot raise up African Gods and become possessed. Of course when this safe rhythm came back to the Ghanaians via West Indian they were very excited, for even though this rhythm was not polyrhythmic, it still had the syncopations and off-beats of African music. So at first the Ghanaians brass bands musicians were playing in strict European ‘oompa oompa’ time – but later modeled themselves on Caribbean marching music with its syncopated Afro-Caribbean time.

Adaha and Highlife

So the Ghanaian musicians of the coast started to play Caribbean rhythms and also Caribbean songs. This led to the development of an Africanized form of brass band music called Adaha in the 1880s – which is the earliest example of what we now call ‘High-life’ – the name actually being coined in the 1920s when Adaha and other street songs were beginning to be played by the ballroom dance orchestras of the local elites and high-ups.

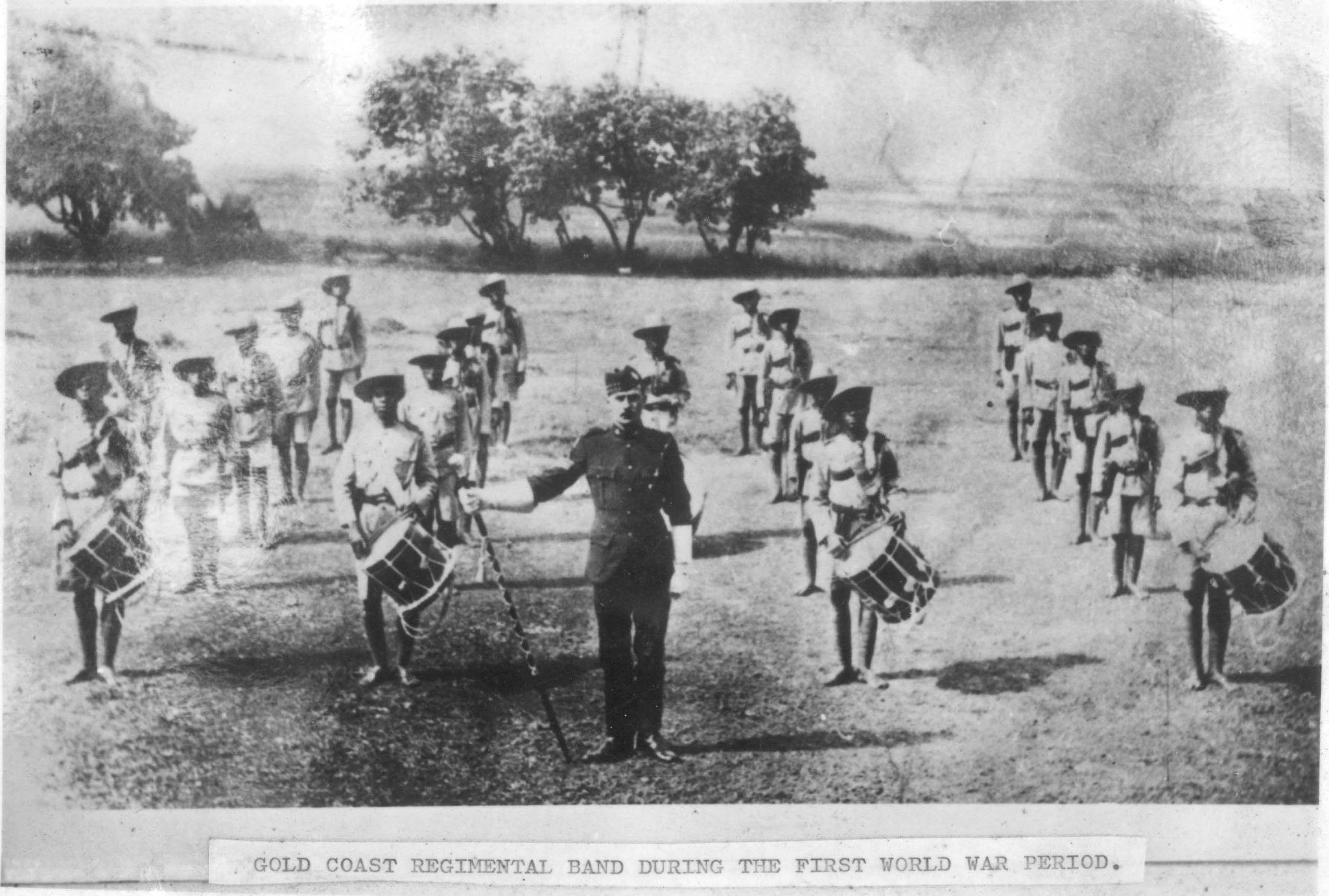

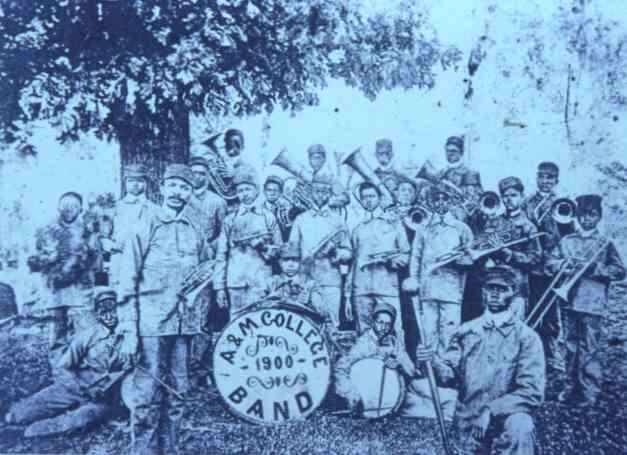

In this picture we see that the musicians are wearing military uniforms, but they are not military people. It was simply the uniform of the music. They managed to turn military music into recreational music that had nothing to do with warfare.

Music went inland

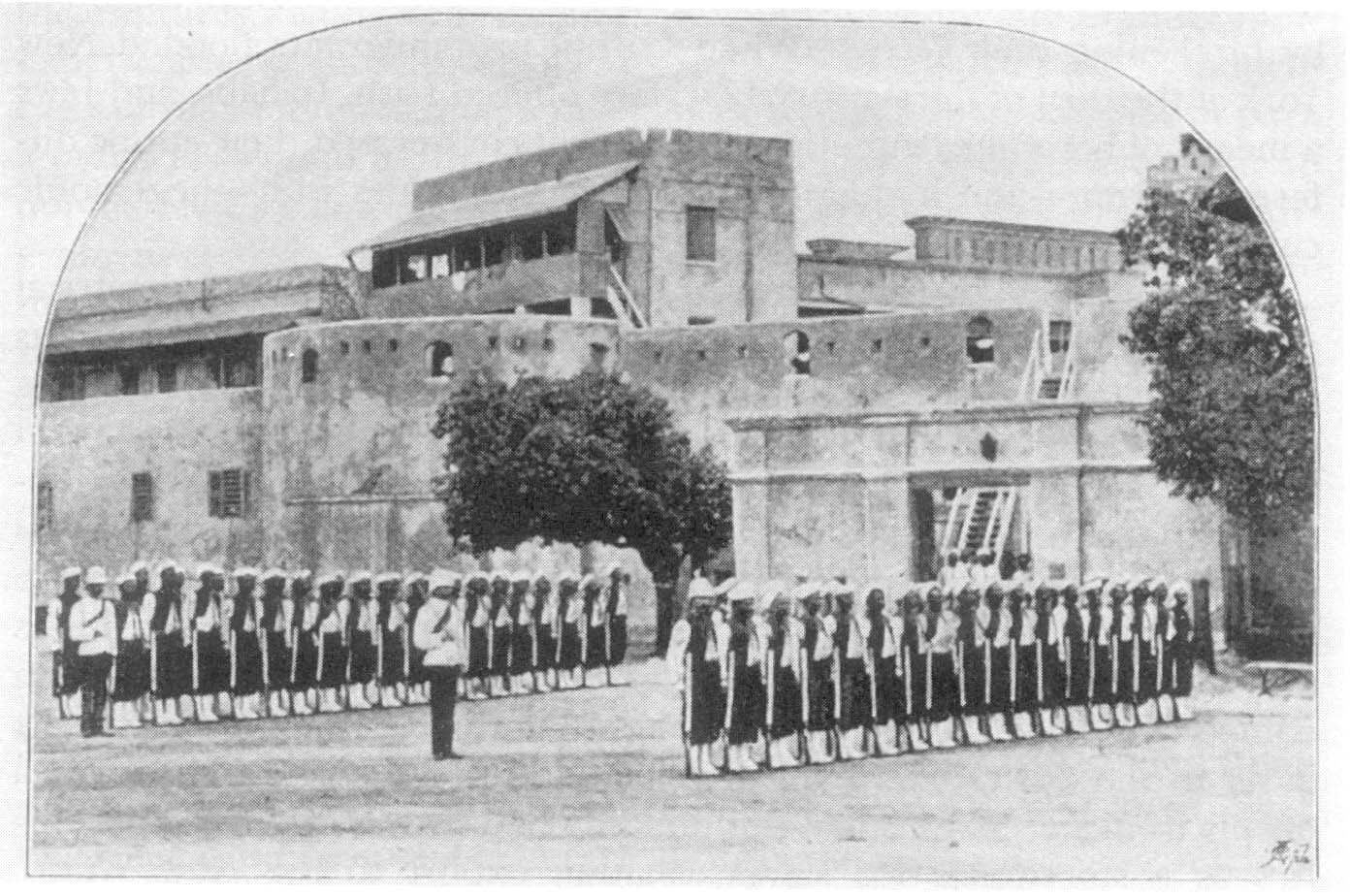

Local Adaha brass band music was created in the coastal port towns of Cape Coast and Elmina. Then the music went inland, into the villages where it became indigenized. This is a photo of a village brass band.

Adaha music in fact went through a series of increasing Africanisations. First the local frame drums and voices replaced the brass bands instruments, because they were too expensive, but they kept the military type uniforms of military derived Adaha brass bands. They invented this music in the 1930s and it was called Konkoma or Konkomba. You can march to it, dance to it, but no brass instruments, no western drums. And this poor-man’s marching music spread throughout southern Ghana as far as eastwards as Nigeria.

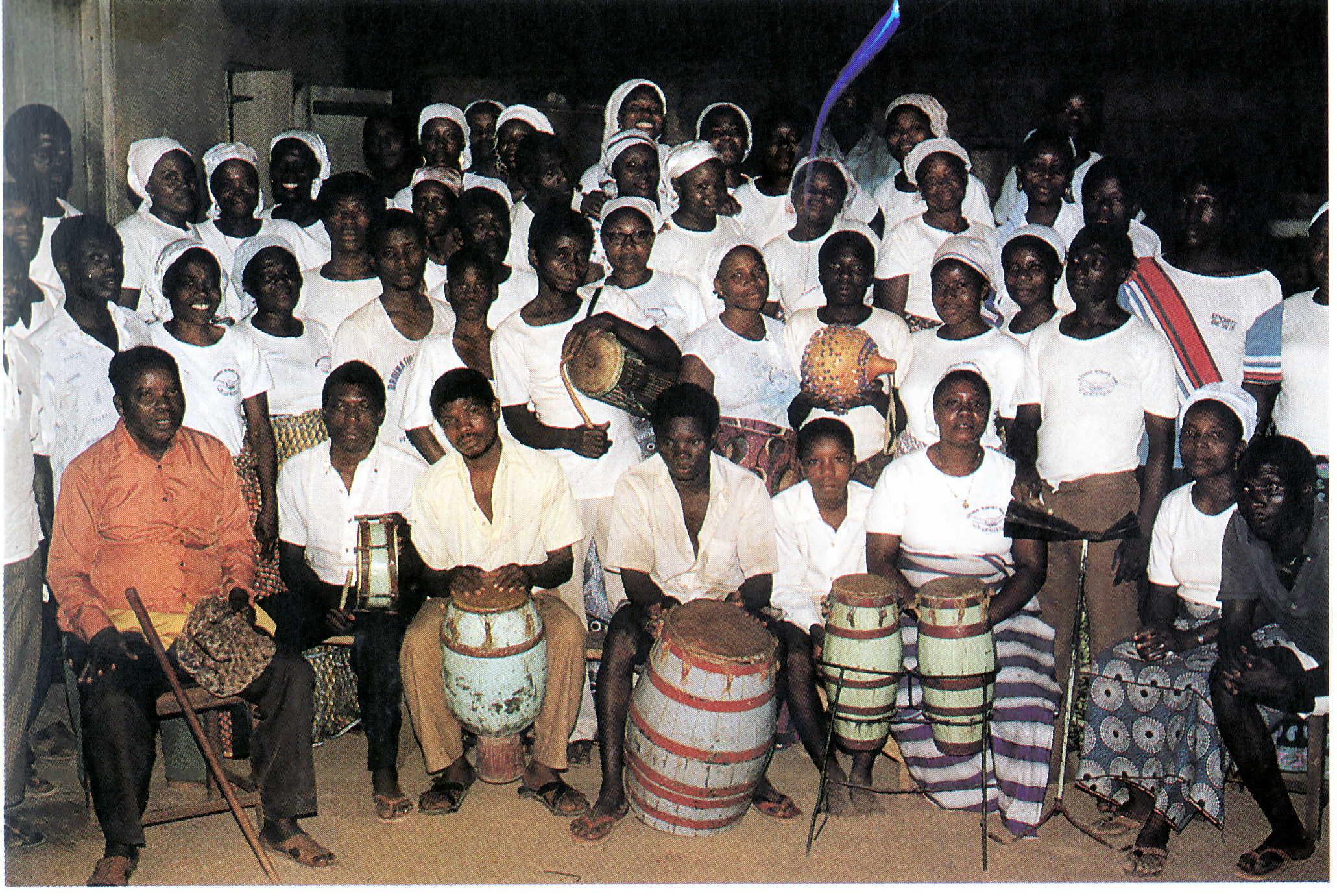

The second stage of the increasing Africansiation of Adaha music occurred when Konkoma moved east from the Fanti area and became popular in the Ewe speaking Volta Region of south-eastern Ghana. There Konkoma, in turn, became ‘Ewe-ized’ as it combined with local Ewe music to become what is called Borborbor music. This Ewe recreational drum-dance music was created in 1950 by a group, originally playing the Konkoma. But they started to use traditional type peg-drums instead of frame-drums.

From the photo you can see these local drums – but you can also somebody holding a Western type of side-drum, but this is not an imported drum, it is a copy of a military side-drum (called the ‘pati’) that was also used in Adaha bands. So this drum still shows a sort of connection with the brass band tradition. Although not shown in this photo most Borborbor bands cannot do without a single bugle or trumpet – again a distant connection the military tradition.

Besides the local and Ewe drum another traditional feature of Borborbor is that it involves a traditional anti-clockwise ring dance, and not marching. Despite all the polyrhythmic drumming you can notice the bell pattern of Borborbor is the old West Indian Rhythm (claves) which as I mentioned earlier is itself is based on an African root rhythm that went to the West Indies and then returned home to Africa.

To sum up we see that local Adaha brass band became increasingly indigenised from the period when it was first created in the 1880s to the Konkoma of the 1930s and Borborbor of the 1950s. I should add that the progressive indigenization of brass bands music also took place in other parts of Africa. For instance Kenya and Tanzania there was a tribalised forms of British and German regimental music called Mbeni that appeared from the late 19th century and particularly just after the First World War when colonial East African soldiers returned to their home towns and villages.

Jazz from New Orleans

Here we will move on to the parallels between West African brass band music and jazz. Of course jazz was born in Louisiana and New Orleans through the Black marching bands, Black funeral bands and the up-tempo syncopated ‘second line’ procession coming back from a burial. Maybe some people don’t realize how Black Americans got access to military brass band music in the first place. Of course it was during the American Civil War when 200,000 African American were recruited into the Union Army.

Before that time it was very difficult for African American to get access to Western military instruments. The whites didn’t want them to use these instruments for warfare or rebellion or for even marching around the streets. It was only during the 1860-5 Civil War that large number of Blacks got access to these instruments and so after the Civil War there was a craze in America for marching bands, including black marching bands, and particularly in Louisiana where jazz was born.

Tribalized and African-Americanised forms of brass band marching music

As mentioned western brass band music was tribalised or indigenised in Africa into Adaha and Mbeni whilst in America it became jazz. So we get repeated examples of either Africans of African Americans hijacking western military brass band music and turning it into recreational music, whether jazz, adaha or mbeni.

This brass band is W.C. Handy’s group and as you can see they are wearing military type outfits and this was typical of African American marching bands and even some ragtime and early funeral jazz bands. These were not soldiers but it demonstrates the military origin of these forms of Black marching bands music. As noted from the earlier pictures of adaha and mbeni bands the performers also wore khaki or military like uniforms.

Besides the fact that these African and Black American forms of syncopated and polyphonic brass band music all have connections with western regimental bands, another parallel is that they all developed from around the same period, i.e. the late 19th century, for is about this time Buddy Bolden and the others were also creating jazz in the US.

By some a sort of miracle Black Americans and Africans were able to hijack the very core of European and American might – which is its military – and turn its music into in something Africans or African Americans could do syncopated marching to – or dance and swing to. These Black peoples on both sides of the Atlantic and at the same time transmuted military into recreational music and literally turned swords into ploughshares.

Impact of Jazz on Dance Band Highlife

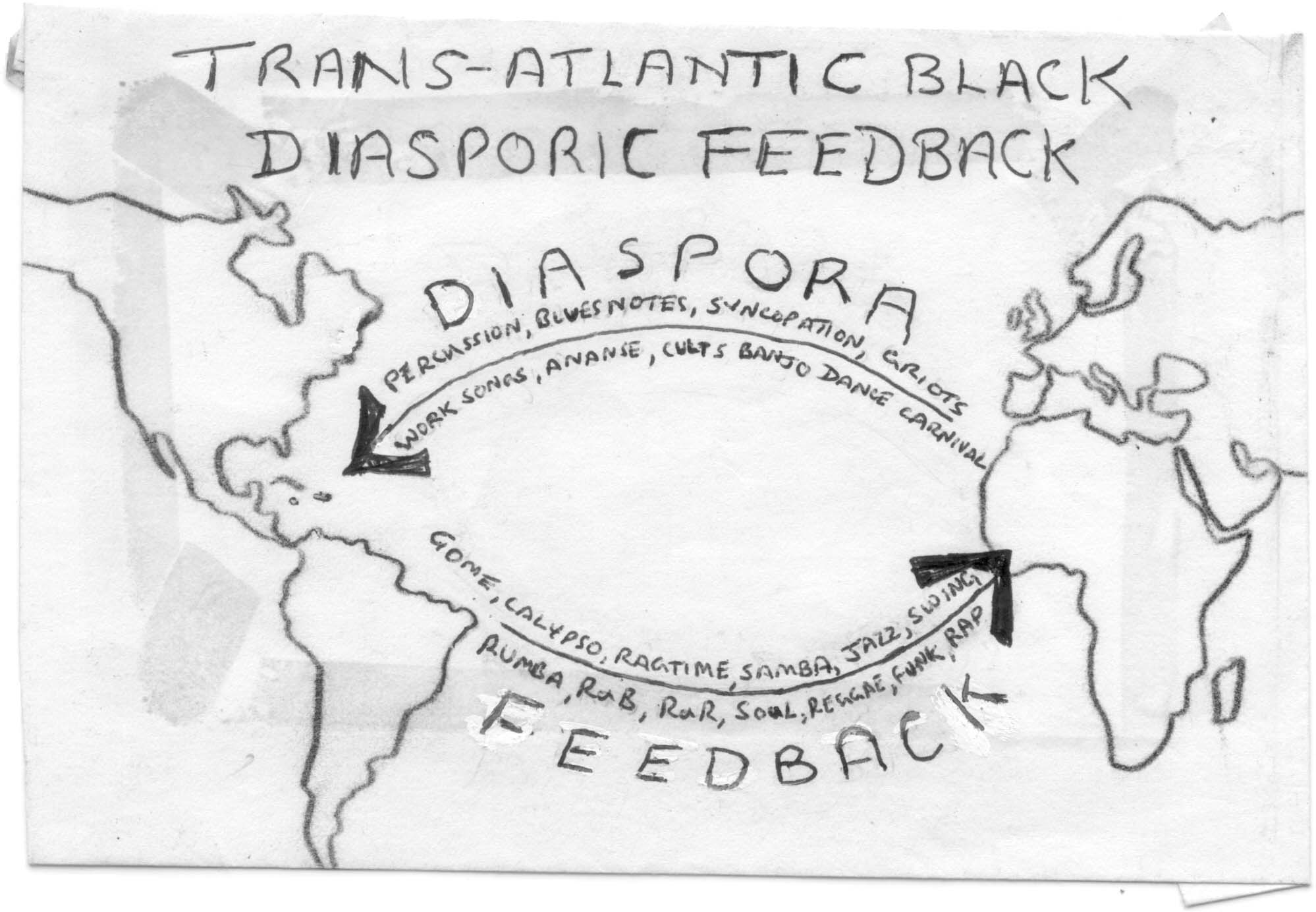

We are coming to the second topic of my presentations which is the direct connection between jazz and African popular music – and in particular the Highlife of Ghana and Nigeria. An this needs to be put into the context of African music going to the New World in the days of slavery and then the creation there of various transmuted African American, Caribbean, Latin music idioms that as can be see from this diagram were returned to Africa.

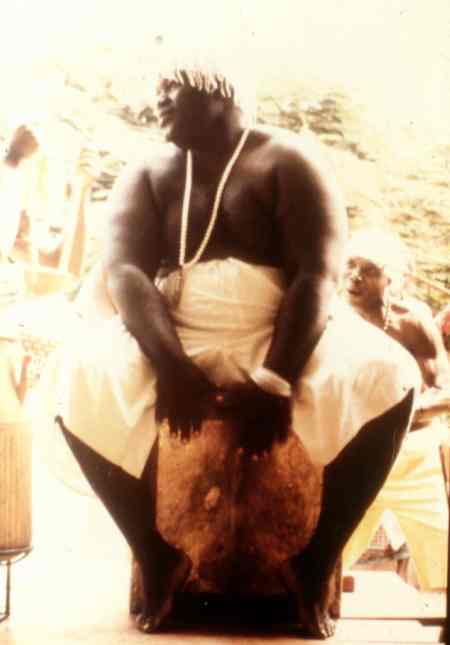

We will talk in detail about the impact of Swing-Jazz on Africa during the 1930s and 40s – but long before this came Jamaican Goombay (or Gumbe, Gome) music that was the first form of Black New World music to return to Africa. If you look here at the picture, you can see the goombay Frame drum.

This is the oldest example that we have of a black Caribbean music coming back to Africa. Normally you think drums going from Africa to the West Indies. In case of the Goombay drum, however, it is the other way round. The Goombay drum is a modified African drum invented in Jamaica in the late 18th century that was taken by freed Jamaican slaves or maroons to Freetown in the West African country of Sierra Leone in 1800 and then from there disseminated into about 17 West and Central Africans countries.

So you can push the story of the musical reconnection, the music of the Black Diaspora coming back to Africa to 213 years. This pushes the whole story of African popular music way way back in time. But for this presentation we’ll start in the 1940s when during the Second World War British and American soldiers brought Swing music with them.

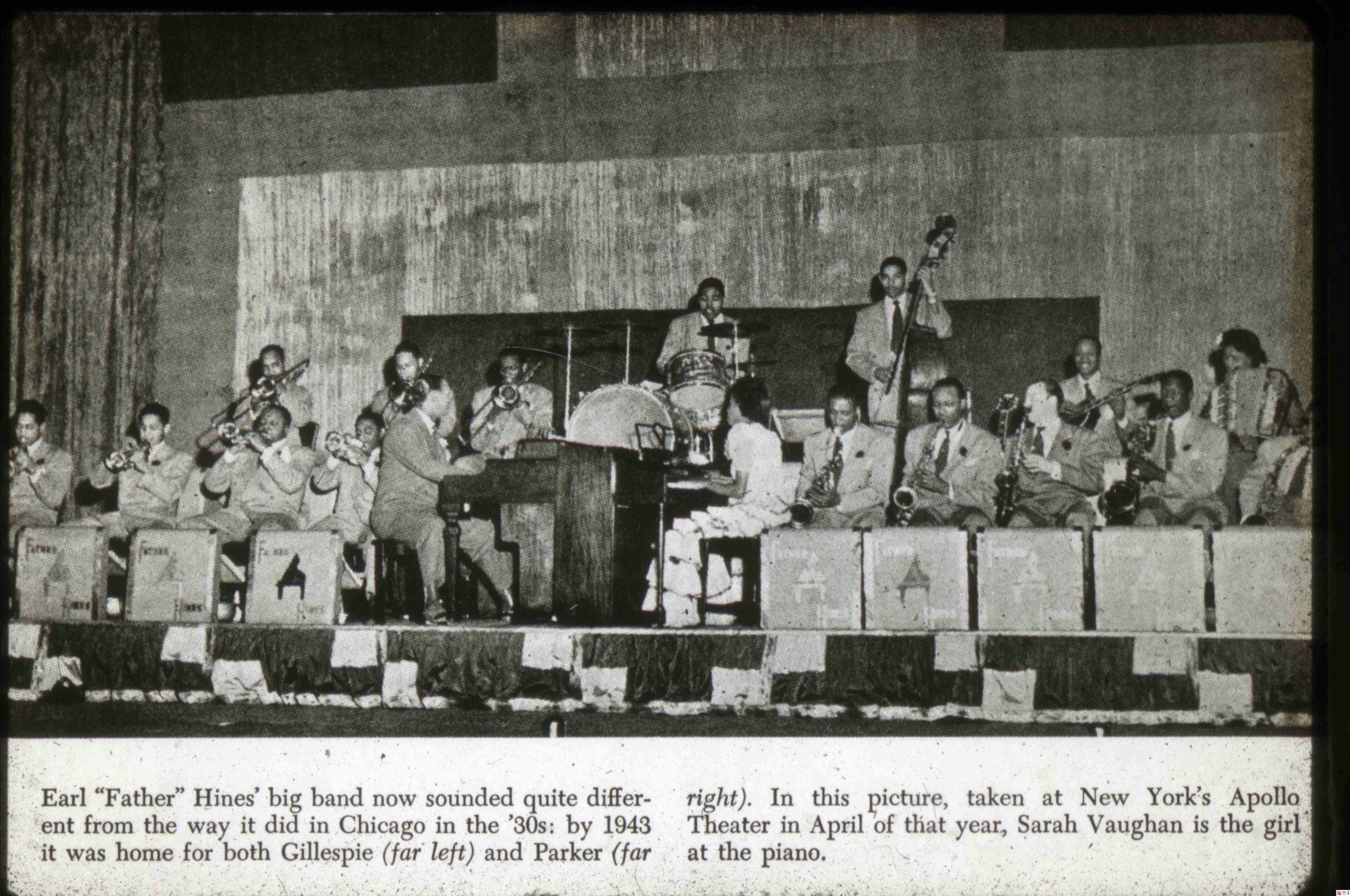

In this picture of the Earl Hynes band we see Sarah Vaughan at the piano and also the young Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker at the extreme ends. So this is the music that was popular during the Second world War and naturally enough it was brought to Ghana, Nigeria and other African countries involved with the allied war effort.

Swing in Ghana

What happened in Ghana was that there was an important dance-band called the Tempos. You see the American and the British soldiers not only wanted to listen to swing records whilst hanging around bars, but they wanted to hear live swing music. So in the early forties they formed band like Sergeant Leopard and the Black and White Spots and the Tempos Band in Accra which consisted of white soldiers and trained Ghanaian dance band musicians. And these mixed bands played swing-jazz music for the troops. The Tempos survived the end of the war when the British and the Americans left in 1945-1946.

Swing and Highlife

Of course the Tempos was already playing swing music, but when it became an all Ghanaian band they also started to play highlife which is the popular music of Ghana.

If you look at the band itself it looks like a small swing combo and it is E.T. Mensah holding the trumpet, who became the group’s leader after the war. The music they played was influenced by swing music and this recording was made around about 1950. The person in the left-hand corner with the dark glasses was the Tempos drummer Guy Warren (Kofi Ghanaba). E.T. always told me that whenever they were playing highlife Warren would play with one hand, but if they were playing jazz he played with all his feet and hands. He was basically a jazz freak.

Warren went to England for some months where he played with Kenny Graham’s Afro-Cubist where he learnt to play Cuban percussion. So he brought the Cuban congas and the bongos back to the Tempos band. Previously the Tempos was only using trap-drums and no African drums. But then they got Afro Cuban drums, which in a sense are somewhat Africa. So the Tempos was able to start to integrate Cuban drums and this one of the things that made the Tempos so sensational at the time.

Within a few years of this highlife dance-bands like the Tempos and others modeled on it were using actual African drums. So Cuban drums acted as a stepping-stone back to African drums. For example here’s a picture of King Bruce’s Black Beats Band around 1953, that was inspired by the Tempos and you can that they include an African drum.

Africanisation of percussion

What happened was that bands up until the time of the early Tempos wanted to be modern, so they didn’t use traditional African drums at first. Of course Cuban drums are imported, so the Tempos and other dance bands did use them as they were modern and from abroad. But after a while these drums broke down and the dance-band musicians realized why not substitute local hand drums.

So this began the process of the Africanisation of the percussion section of the Ghanaian dance bands. It was Guy Warren who did this quite inadvertently, for as I mentioned he was more interested in jazz, but this included BeBop and the Cuban influenced CuBop. In fact his fascination with modern jazz took him to America in 1955 where met and jammed with Charlie Parker just a few months before Parker died.

Afro-Jazz

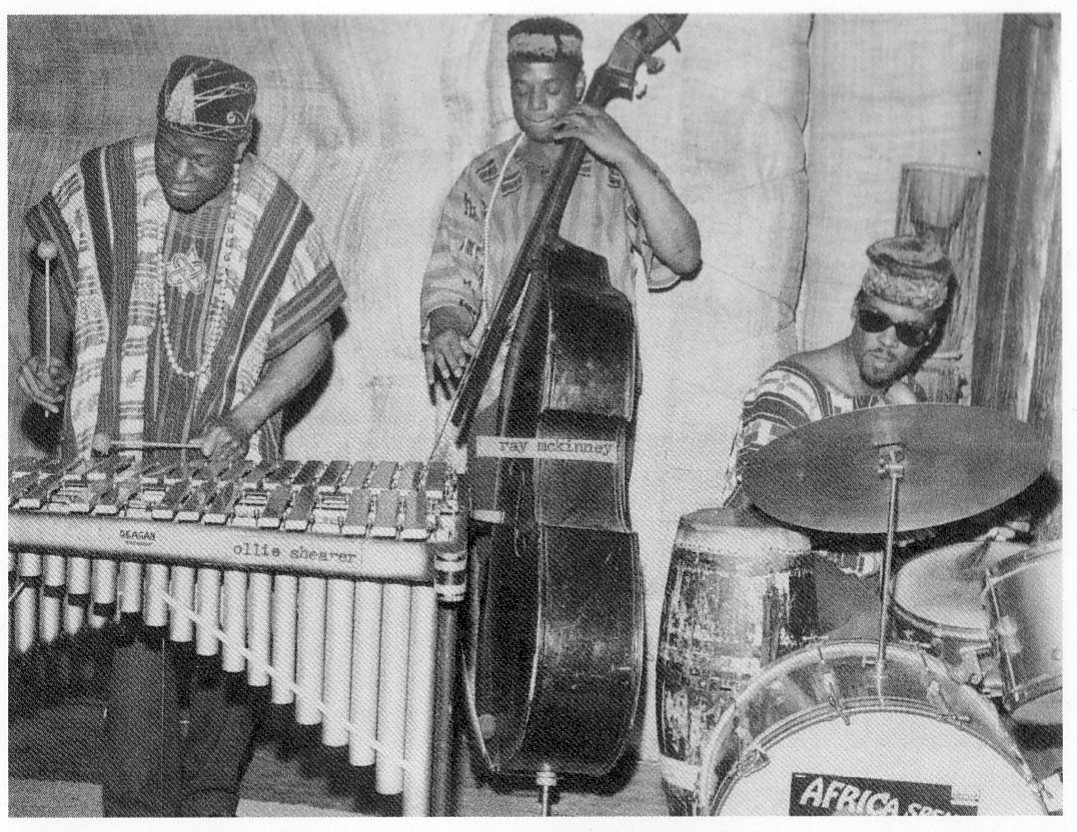

Let me say a few words more about Guy Warren. He launched a number of Afro-Jazz albums. The first was called Africa Speaks America Answers that was released in America in 1956/7. So this is quite a long time before Coltrane and other picked up on the idea of using African inspirations. He was there right at the beginning. And he worked with a lot of people like Red Saunders, Max Roach, Thelonius Monk, General Bey and others. This is another picture of him.

So in the States Guy Warren moved away from Highlife into Jazz. Later, when he came back to Ghana (and began calling himself Kofi Ghanaba) he created a Afro-jazz kit made of a collection of different African drums, but also using to foot pedals. African drumming is usually produced by a group of musicians, but although he used African drums Guy Warren turned them into a jazz-like solo instrument with two foot pedals. They are African drums but they are organized as a jazz kit.

Back in Ghana Guy Warren/Ghanaba became a guru for jazz and even rock musicians who visited him from the 1970s – like Max Roach, Ginger Baker, and Randy Western. So that’s the story of a highlife musician who went more deeply into jazz, and in fact became pioneer in Afro Jazz. Because of this he is well known by the older generation of jazz musicians in America.

Louis Armstrong in Ghana

Ghanaba went to America – on the other hand Louis Armstrong came the other way. In fact this great jazz trumpeter came twice to Africa, first to Ghana in 1956 and then he made an African tour in 1960/1.

When he was in Ghana in 1956 he saw a woman at a market in Accra who so much resembled his grandmother that he was convinced his ancestors came from Ghana. In fact in 1960 he actually began the process of acquiring land in Ghana, but he was simply too busy to settle him down. This is a picture of him playing with E.T Mensah the leader of the Tempos band in 1956.

This is also another picture of Louis Armstrong in 1956 when he came to came to Ghana with his wife Lucille and was hosted the Ghanaian Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah – just one year before Ghana’s independence.

Independence struggle

E.T. Mensah supported the independence struggle such as in the song we just heard, Ghana Freedom Highlife. In fact many highlife song recorded in the fifties supported the independence struggle and I have never heard of a highlife song that said we don’t want independence. If there had been such a song it would have been such a flop as no one would have bought it. So the highlife bands band supported Kwame Nkrumah, and Nkrumah in turn supported highlife music and the popular music industry in those days. He also set up recording studios, state bands and encouraged the formation of musicians unions.

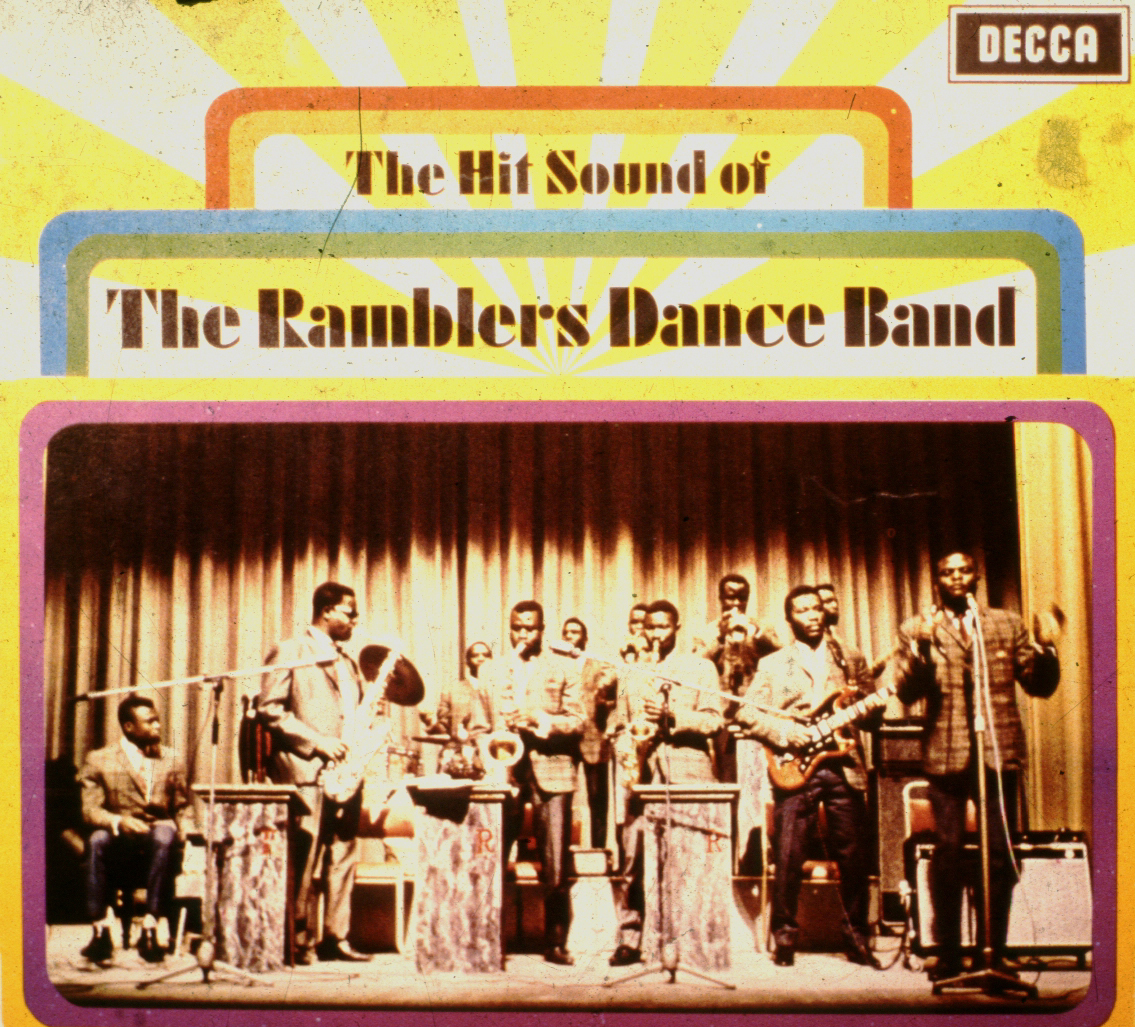

This is an example of another highlife dance band that supported Nkrumah called the Ramblers, one of the many bands that modelled themselves on the Tempos. Then there was the Broadway, Uhuru, the Messengers, Rhythm Aces and so on. I have got a list of 150 of such dance-bands and they all played highlife with a touch of swing and Latin music as well as the Trinidadian Calypso music of Mighty Sparrow and Lord Kitchener, whose records were very popular in Ghana.

So there was a lot of crossovers between calypso and highlife. In fact if you think back to the brass band music that I was talking about earlier, the very earliest form of highlife itself (adaha music) was born out of a fusion of African music and calypso.

Women on stage

Another important thing that E.T. Mensah did he did was that he was the first to put women on to a popular dance-band stage. Julie Okine – and there were a number of other important women singers – played with the Tempos from the mid-fifties. These were brave and daring women in, infact, Julie Okine, wrote the first modern Ghanaian feminist song called Nothing but a man’s slave , which she released in 1957 with the Tempos.

I didn’t ask E.T. Mensah about this reason for this when I was writing a book about him many many years ago. But I believe the reason why these lady singers could break the Ghanaian taboo against women going on the popular stage, was that E.T. Mensah was influenced by American swing and some of the these jazz bands were being fronted by famous Black American lady singers like Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horn, Sarah Vaughan.

So the impact of swing on E.T. Mensah included the role model of black female artists, and this allowed him to take the chance on putting women on stage in Ghana without them being considered as loose women. If anyone you know the story of the famous South African Miriam Makeba, it is exactly the same. She started her career with the Manhattan Brothers, which was sort of a South African swing band and her great heroine was Ella Fitzgerald. So basically black American women superstars created a space in Africa for women popular performers.

Highlife to Nigeria

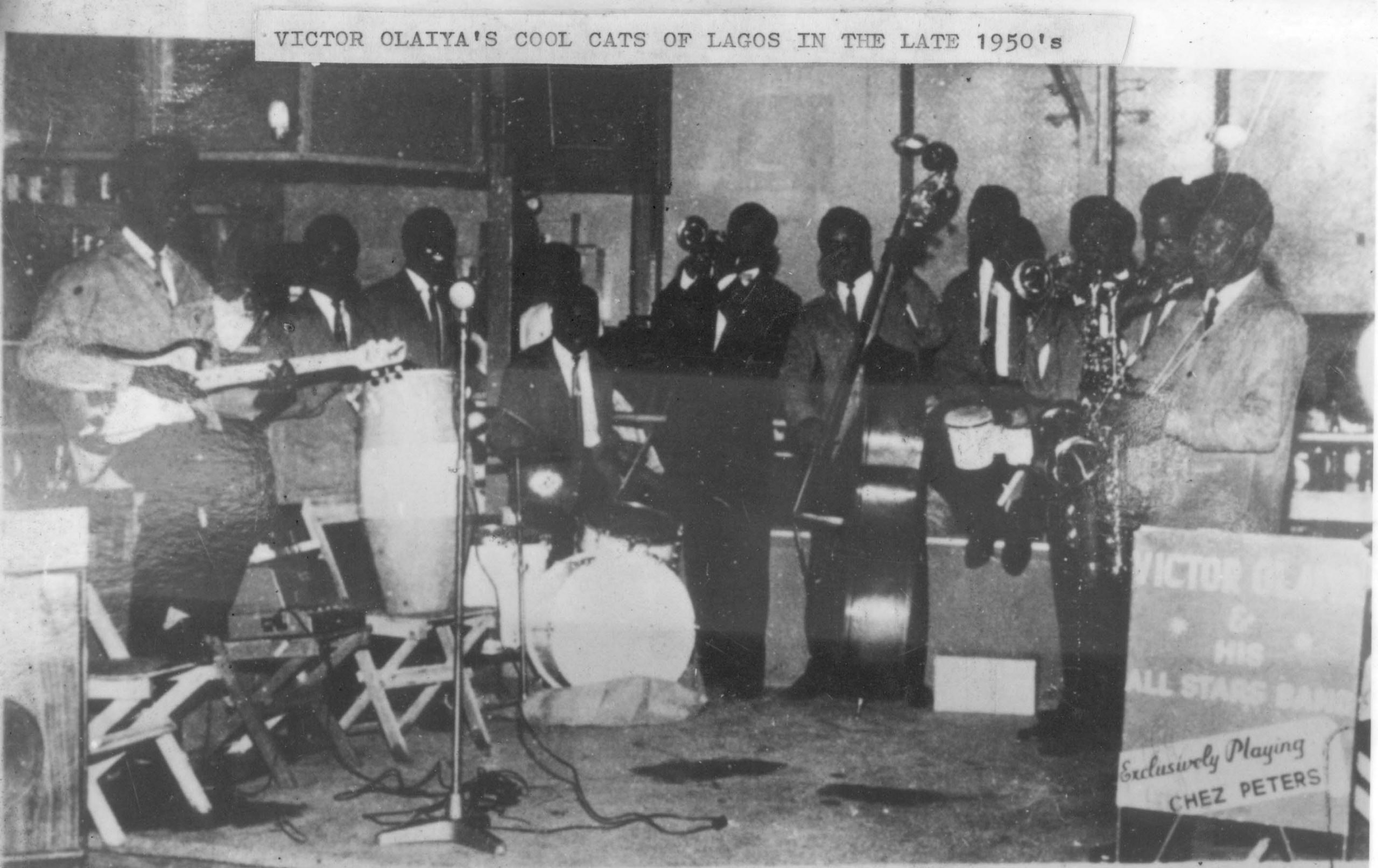

Besides creating a new blend of highlife, supporting the nationalist cause and putting women on stage another important thing about the Tempos band was it was they who primarily introduced dance- band Highlife to Nigeria. In Nigeria there were dance bands after the Second World War but they were so music under the spell of swing – Jazz and that they never got round Africanising swing music. So there was a sensation when E.T. Mensah and his Tempos turned up in Nigeria in 1951 with a swing type dance band that played African music. Nigerian artists like bands quickly followed suite: like Rex Lawson, Bobby Benson and Victor Olaiya.

These are pictures of two Nigerian bands influenced by the Tempos – Bobby Benson Band, Victor Olaiya’s. Luckily enough I met all these guys in the seventies when I was going to Nigeria and I double checked the story with them. There was a rumour going down that highlife was born in Nigeria, but the older generation knew that it came from Ghana and was brought to Nigeria.

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti

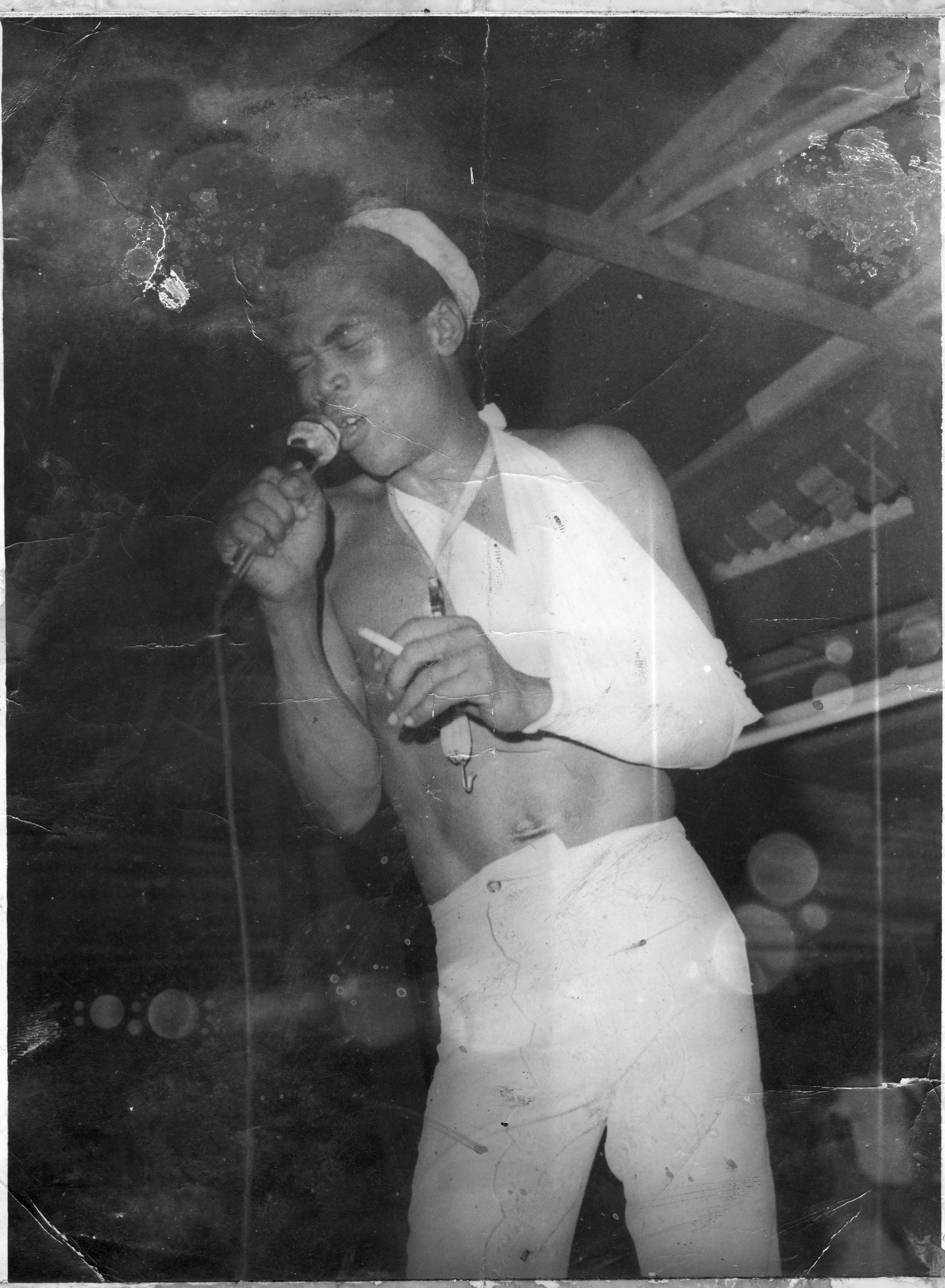

The last point I want to make here is that it was Victor Olaiya’s band was the first professional group band that Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the inventor of Afrobeat music, ever played with. Fela himself started as a Highlife musician with this particular band in the mid 1950s and in the sixties he was always coming up and down to Ghana with his Koola Lobotos band that played a jazzed up form of highlife. Then from the late 1960s he moved from highlife into his own Afrobeat idiom that fused highlife with, modal jazz and soul music. Here’s a photos I took of this militant musicians in 1974 when I was playing with a Ghanaian resident band at his Afrika Shrine club in Lagos.

© John Collins, more about Fela Kuti you can read in Collins’ ‘Kalakuka Notes’

Reblogged this on iRADIO.tt Blog + Journal: Appraisal, Opinion, Information and commented:

John Collins talks about the connections and interconnections between the jazz in America and African brass music. West Indian music and rhythms also had an early influence of this resulting music. Bottom line, when Black people play music, it enriches the World of music.

thanks for the enlightenment. I will like to know if there are any great contemporary brass band music on line to listen to.

What kind of music? There are so many nowadays: like the Brazilian Bixiga 70, or the American Hypnotic Brass Ensemble…