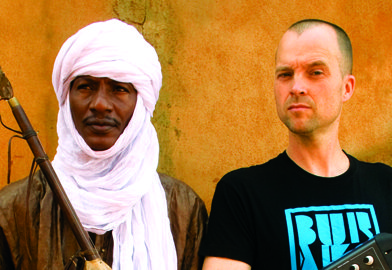

The war in Mali brings a lot of instability and poverty for many people. For the nomadic people like the Tuareg, the situation is even more complicated as we saw in the interview with Ousmane Ag Mossa of Tamikrest on News and Noise! This is also the case for the group Super Onze (or Super 11) from Gao, who is unlike Tinariwen, Tamikrest and others, unknown outside of Mali. They play just one rhythm, Takamba, on traditional instruments like the calebash and the n’goni. But the way they do it is amazingly raw and virtuoso. One of the most adventurous DJ’s in Holland MPS Pilot, aka Horst Timmers – active in the ‘cutting-edge World Music scene’ – got fascinated by Super 11 and found a way to work together with the group. Recently he released their second album on his label Two Speakers. I asked him some questions about how they met, their collaboration and how the situation in Mali affects Super 11.

by Charlie Crooijmans

When and where did you meet Super 11?

“In 2003 I was at the Festival au Désert where reputable musicians like the late Ali Farka Touré were playing and the still very unknown Tuareg group, Tinariwen. There was also a group who played far too loud and too fast. This was Super 11. They were playing a rhythm which is called Tambaka. Amongst the westerners they weren’t discovered yet and completely underrated, but I immediately liked them. I thought that it would be great to meet them again and do something with their music. In 2004 I saw them once more, but I was DJ’ing at night and you have to imagine that the festival is quite chaotic with lots of poor people – and me being white and rich- from remote areas. So I didn’t get the chance to meet. The band also vanished as they split up. After the festival I met some groups who were playing Tambaka and I came closer to the Tuareg. A friend and guide of mine, Papa S, introduced me to them. But it wasn’t that interesting. So my friend suggested that we should go the opposite way, to Gao. Gao is a huge but poor town located on the eastern bank of the Niger River. There I met one of the guys, the n’goni player, and he told me that someone run off with their band name, so they chose to use another name, Super Khoumeïssa. You must taken into account that it’s not a fixed group but a collective that drink tea and play music. Anyhow, they are already known in Mali for more than 30 years. One of the grandpa’s who played in the band had the rights, so we thought that it would be better if they start to use the old name again and do a project together under the name Future Takamba.”

In what way did you participate as a musician?

“I play with my laptop on Ableton Live, using samples and an Midi Controller in order to play live, in real time, to join in the changing tempo of the band. Sometimes the traditional music is the leader, sometimes the electronic music. We were accompanied by VJ Lotte de man showing experimental beautiful visuals from here and there. We played eight concerts in Holland, Belgium and Mali. We also played in Mali at the festival Au Niger. The people at the shore enjoyed it so much. Beside that, we recorded an album with their traditional Takamba repertoire which is released on Xango. We rented a house in Bamako where we recorded and rehearsed during two weeks.”

What is the meaning of Takamba?

“Takamba means gesture of the hand. The music is performed while sitting, the dancing is also seated. It’s a courting dance. The man and woman sit face to face and dance with their hands. If they are standing, there is a line of men and women and they cautiously dance while nearly touching the shoulders. The men and women are wearing boubou’s, dresses with big shoulder, which make it seem more dramatically. They perform Takamba at any kind of celebration, weddings, circumcisions, elections, and so on. It depends on the situation what they, as a griot, have to tell. But as they are genuine musicians they do not only play at parties, but also in the more silent moments. So for the first album I asked them about all the kinds of Takamba tunes they play in whatever situation.”

The second album is the re-release of a tape from 1994, why?

“I wanted to show their music how it was recorded normally. The tape I used for the second album is a tribute to Yehia Le Marabout. He is a kind of a Islamic healer. He assigned the musicians to play and record this tape. I got eight tapes of Henriette Kuypers Touré (the widow of Ali Farka Touré). She used to go very often to the home cassette factory of Samba Afro Cissé, a famous tape vendor in Bamako. The recordings occurred at the local radio stations. Tapes, by the way, are being pushed away by the CD’s from 2004 on. Which is a shame because a tape recorder is much more resistant against the dust and sand than a CD-player.”

How is the situation of the musicians right now?

“The situation is extremely difficult. They became very dependent. The war destroyed the infrastructure of the rites de passage. Families have been torn apart so there is not much to celebrate, so the artists can’t earn their money with their music and dance. There is a lot of misery. Wearing a turban is very dangerous, as the military constantly aims on them in the North of Mali. Because of this situation some people of the different tribes choose for themselves and steal from others. Like, the military who committed the coupe have been looting millions of CFA’s public money. So at one time the Ministry has no money for education. And in a dry and poor place like Gao which already has been neglected since decades, a lot of narco-terrorism is going on, hidden under the flag of some religion. The economic situation is already very feeble and if the Bambaras and the military just take care of their own business, the economics will collapse soon.”

Do you think that the elections will bring any solutions?

“The elections are far too early. I am not an expert in this, but anyone who is involved in one way or another will say the same. There is a group on Facebook – Americans and friends in Mali, they are formed around Christian Peace Corps members, where you can get news and information about what’s happening in Bamako and Mali.”

Are you in contact with the musicians?

“Yes, I am in close contact. For them family is very important. I try not to call too often. Like every two weeks and not more I am not able to support them. They have to find a way to make money in a different way, with micro credits. As griots they are kind of used to get money in all ways around their work, but now they are even not able to make music. Actually there were well to do. What I offered them is not much compared what they usually get. But at least I gave the band at least a boost.”

How can we help?

“By buying the DIGITAL release and spreading the word. But only if you like Takamba music! The money will go straight to the band.”

Why is this DJ so obsessed with poverty? In his conversation he mentions how poor the people were, how much poverty was in the places he visited. How ‘rich’ is he himself?

He went to find music but is so focused on ‘poverty’. Rich musical heritage is in fact also great wealth. This guy shouldn’t be in Africa making music.